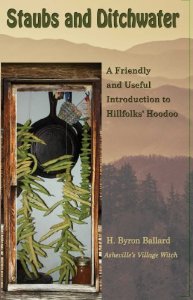

Recently I attended my first neoPagan gathering in over a decade; while there, I picked up Staubs and Ditchwater by H. Byron Ballard (Silver Rings Press, 2012), a book on Appalachian folk magic. As I read, I ran across a statement that brought up an important issue: cultural appropriation, or as Ballard puts it, cultural strip-mining.

Ballard writes, “We tribeless white people learn dances and songs from other cultures that seem deeply spiritual to us, though we don’t know their context or deeper meanings, we just like the way they look or sound or make us feel. We think they’re cool.” (p. 12)

I’ve made no secret that my Tufa were inspired by the stories of the Melungeons, before those tales were thoroughly dissipated by modern DNA testing a couple of years ago. They fascinated me from the first time I heard about them as a child, and I’d always wanted to write about where they might’ve come from and how they ended up here.

But when it came time to actually write The Hum and the Shiver and its follow-up, Wisp of a Thing, I ran up against something my parents drilled into me: namely, good manners. Or, as my late father put it, acting like you’ve been to town before.

In high fantasy, secondary-world fantasy, or whatever term you choose, you make up everything. Geography, climate, religion and politics are created from scratch. They may echo or show the influences of real world inspirations—it would be strange if they didn’t at some level—but they’re still fictional. You can do or say anything you want about them.

In fantasy set in the real world, the rules are a little different. If you write about Native Americans, you’re writing about people who really exist, and might take exception to your depiction of them. If you write about a minority that you’re not a part of, you have to be exceptionally sensitive to their history of being reduced to stereotype and misrepresentation. Well, I suppose, you don’t have to; but if you’re not, then you’re kind of a jackass. Or a strip miner.

So I knew almost from the get-go that I wouldn’t write about the actual Melungeons. Besides, I’d already formulated a lot of the ideas that eventually became the Tufa, and they didn’t jibe at all with the real history (as it was known ten years ago when I was doing all this initial thinking). So I borrowed the bare bones of their story, and put the flesh of my own fictional group over it.

There are creative reasons for doing this as well: when you’re making stuff up, as opposed to recreating reality, you can change things as they’re needed to advance the story. I wrote two novels set in real 1975 Memphis, and did tons of research to make sure I got it as correct as possible. But with the Tufa novels, I made sure everything was invented, so that the locale, geography and all other details are entirely out of my own head.

I had a similar challenge in my Firefly Witch stories, which are also set in the real world. I wanted to reference Native Americans, but hesitated to use any actual tribes. I felt, simply, that I wasn’t qualified to depict the practices of any real Native Americans. So instead, I invented my own, the Lo-Stahzi. I could give them whatever history, lore and practices I wanted.

So there are practical reasons for doing it this way. But there’s also the fact that it’s just polite. As Prince Feisal says in Lawrence of Arabia, “With Major Lawrence, mercy is a passion. With me, it is merely good manners. You may judge which motive is the more reliable.”

Or, as Ballard eloquently puts it in her book: “Don’t be a cultural strip-miner.”

Alex Bledsoe is author of the Eddie LaCrosse novels (The Sword-Edged Blonde, Burn Me Deadly, Dark Jenny, Wake of the Bloody Angel), the novels of the Memphis vampires (Blood Groove and The Girls with Games of Blood) and the Tufa novels (The Hum and the Shiver, and the forthcoming Wisp of a Thing).

I was a bit shocked, and others even more so, at how much ‘strip mining’ of other, earlier faiths, we found in Christianity when our Bible Study group looked at a wide range of different religions one summer.

Sometimes I feel that every culture reaches back and picks and chooses what it likes from those who came before.

The problem with an injunction against “cultural strip mining” is that it presupposes that one person (it always comes down to individual action, even if multiple individuals are acting together) can “own” understanding over a cultural group (and sometimes its not even their group) and exercise a heckler’s veto.

That isn’t to say you couldn’t write a depiction (thinly veiled, thickly veiled, or unveiled) of a culture that was awful, whether that culture was Melungeon, white hillbilly, or eastern Slav. But the basis for criticizing that depiction would be that it is awful. I.e., it would be entirely rooted in the thing, the depiction, not the who, of you or of me.

By the way, I read Hum and Shiver over the holiday weekend and very much enjoyed it and look forward to the next installment.

“Strip-Mining” is so awful a metaphor that it’s impossible not to think that it is deliberately awful and deceptive. Nothing a creator can do can actually damage the mountain here.